London’s Tower of London isn’t just another historic site tucked between the Thames and Tower Bridge. It’s a place where royalty met betrayal, where heads rolled on cold stone, and where the weight of centuries still hangs in the air like the damp mist off the river. Walk through its gates, past the Beefeaters in their red and gold uniforms, and you’re stepping into a prison that held some of the most powerful-and most doomed-figures in British history.

More Than a Tourist Spot: A Living Prison

Many visitors think of the Tower as a photo op with the Crown Jewels or a quick stop between a Southwark pub and a Thames river cruise. But for over 900 years, it was a place of confinement, interrogation, and execution. Unlike modern jails, this wasn’t just for petty criminals. It held kings, queens, bishops, and traitors-all of whom had something to lose. The Tower didn’t just imprison people; it erased them from history, sometimes without a trial.

Think about it: if you lived in London in the 1500s, you’d know someone who’d been taken to the Tower. Maybe a neighbour’s cousin, a merchant who fell out of favour with the king, or even a relative caught up in religious upheaval. It was part of the city’s fabric-like the Bank of England or the London Underground-but far more terrifying.

Anne Boleyn: The Queen Who Lost Her Head

Perhaps the most haunting story belongs to Anne Boleyn. She wasn’t just Henry VIII’s second wife-she was the woman who changed England’s religion, gave birth to Elizabeth I, and was executed on Tower Green in 1536. She didn’t die on a public scaffold like others. She was beheaded privately, on a small patch of grass just outside the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula, where her body still lies.

Her crime? Alleged adultery and treason. The evidence was flimsy. The real reason? Henry wanted a son, and she’d failed to produce one. He’d already set his sights on Jane Seymour. So Anne was arrested in the Queen’s apartments inside the Tower, interrogated by men loyal to the king, and sentenced to death within days. Her final words were dignified. She asked for mercy, not for herself, but for the kingdom.

Today, you can stand where she walked. The Queen’s House still stands. The same narrow corridor she took to the scaffold is now part of the guided tour. Locals who’ve lived in Southwark or Wapping for years still whisper about her ghost-some say you can hear her footsteps on the stone when the crowds leave.

Thomas More: The Saint Who Refused to Bend

Then there’s Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor, the brilliant lawyer, and the Catholic martyr. He was friends with Erasmus, wrote Utopia, and served Henry VIII faithfully-until the king broke from Rome. More refused to swear an oath acknowledging Henry as head of the Church of England. He didn’t fight. He didn’t flee. He just said no.

He was imprisoned in the Tower for over a year. His cell was small, damp, and cold. He wrote letters to his daughter, Margaret, and kept a small garden of herbs in his window. He was executed in 1535, just like Anne. His head was displayed on London Bridge, a warning to others. His body was buried in the same chapel as Anne Boleyn.

Walk past the chapel today, and you’ll see his name carved into the stone. Many Londoners still visit on his feast day, July 6, leaving flowers or lighting candles. He’s not just a historical figure-he’s a symbol of quiet resistance, something many in this city still respect.

The Princes in the Tower: A Mystery That Still Haunts

Some of the most chilling stories involve children. In 1483, the young King Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York, were taken to the Tower-officially for their protection while their uncle, Richard III, prepared for coronation. They were last seen playing in the gardens. Then they vanished.

No bodies were found. No confessions. But the story stuck. Rumours spread that Richard III had them murdered. Shakespeare turned it into a play. Even today, archaeologists debate whether bones found in 1674 under the stairs of the White Tower were theirs. They were buried in Westminster Abbey, but the truth? Still unknown.

Locals in the City of London still talk about the boys. Some say you can hear faint laughter near the Bloody Tower on quiet evenings. Others say if you stand at the window where they were last seen, you can feel the chill of a betrayal that changed the course of a dynasty.

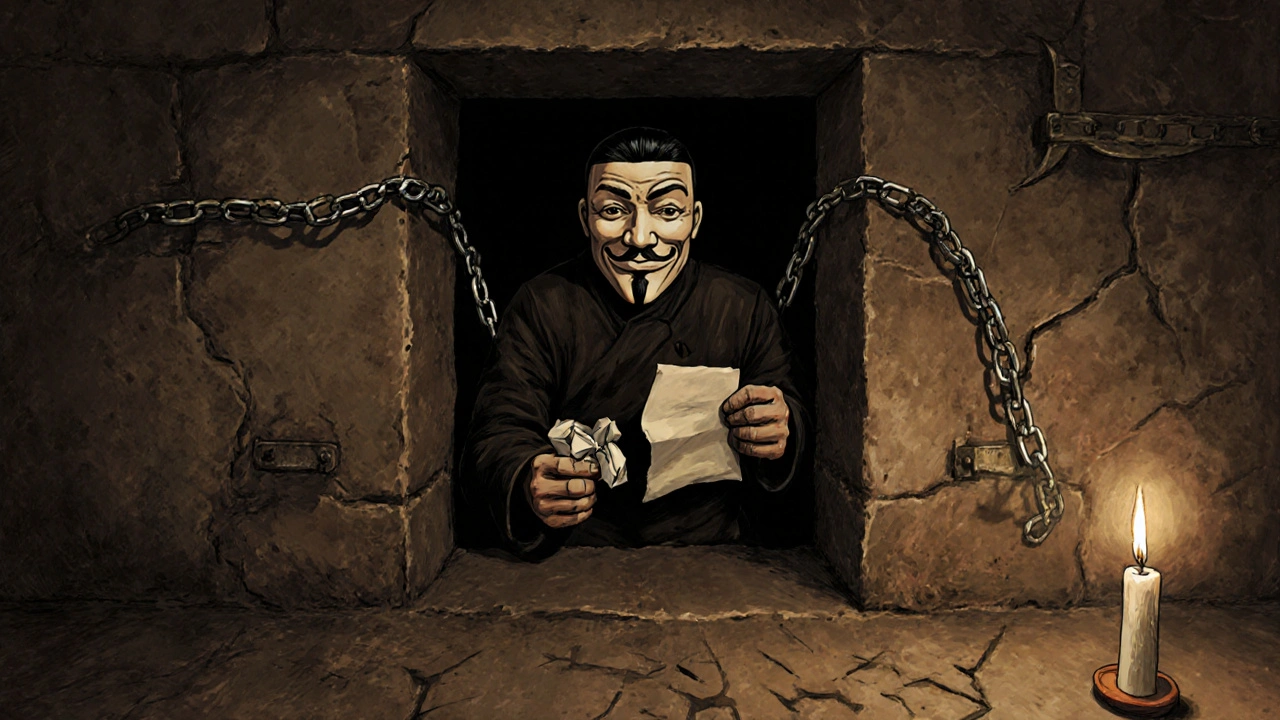

Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot: A Bomb That Almost Blew Up Parliament

Fast forward to 1605. A group of Catholic conspirators, led by Guy Fawkes, planned to blow up the Houses of Parliament during the State Opening. Their goal? Kill King James I and restore Catholic rule.

Fawkes was caught in the cellar beneath Parliament with 36 barrels of gunpowder. He was dragged to the Tower, tortured on the rack, and confessed after days of agony. His name became synonymous with rebellion. Every November 5, Londoners still light bonfires and burn effigies of him-especially in places like Lewisham, Greenwich, and even near the Tower itself.

His cell in the Tower still exists. It’s tiny, barely big enough to lie down in. The walls are stained with damp. You can see the marks where the chains were bolted. He didn’t break easily. He broke because he was made to.

Why the Tower Still Matters to Londoners

Today, the Tower is managed by Historic Royal Palaces. It draws over 3 million visitors a year. But for Londoners, it’s more than a museum. It’s part of our identity. We walk past it on the Jubilee Line. We see it from the Thames Path. We know the names of the Beefeaters who guard it-like the one who’s been there since 2008 and still tells kids the same ghost stories his grandfather told him.

It’s not just about the Crown Jewels, though they’re dazzling. It’s about the people who lived-and died-here. The Tower reminds us that power is fragile. Loyalty can be bought. History isn’t written by the winners. It’s written by those who survived long enough to tell it.

If you’ve ever stood on Tower Bridge at sunset, watching the light hit the White Tower, you’ve felt it. The air changes. The noise fades. For a moment, you’re not in a bustling city. You’re in a place where kings were imprisoned, where mothers wept, and where silence still speaks louder than any guidebook.

What to See When You Visit

- The Crown Jewels - Guarded by Beefeaters and laser sensors, they’re displayed in the Waterloo Barracks. Don’t rush. Look at the Imperial State Crown. It’s worn by the monarch at every State Opening of Parliament.

- The Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula - The burial place of Anne Boleyn, Thomas More, and others. It’s quiet, unassuming, and often overlooked. Sit for five minutes. Listen.

- The Bloody Tower - Where the Princes disappeared. The view from the window is the same as it was in 1483.

- The White Tower - The original fortress. Built by William the Conqueror. The oldest part of the complex.

- The Torture Exhibition - Real instruments used on prisoners. Not for the faint of heart. But it’s real history, not Hollywood.

Visit on a weekday morning. The crowds are thinner. The Beefeaters have more time to talk. Ask them about the rats that used to run through the dungeons. Or how the Thames used to flood the lower levels. They’ve heard it all before-but they still tell it like it’s the first time.

How to Get There

The Tower is easy to reach. Take the Tube to Tower Hill (District or Circle line), or walk from London Bridge station. If you’re coming from the South Bank, follow the Thames Path-it’s a 20-minute stroll past Shakespeare’s Globe and the Tate Modern. Bring a coat. It’s always windier here than in Covent Garden.

Buy tickets online. Lines can be long. And if you’re a London resident, check if you qualify for a discount through your borough council. Some, like Southwark and Tower Hamlets, offer free or reduced entry for locals.

Final Thoughts

The Tower of London doesn’t just tell stories. It holds them. In its stones, in its chapel, in the rusted chains still on display. It’s not just a relic. It’s a mirror. And if you listen closely, you can still hear the echoes of those who walked here before us-men and women who thought they were safe, until they weren’t.

Next time you’re in London, don’t just snap a picture. Stand where they stood. Feel the cold stone. Remember their names. Because history isn’t just in books. It’s right here-in the heart of the city, behind the walls, waiting to be heard.

Who were the most famous prisoners in the Tower of London?

Some of the most famous prisoners include Anne Boleyn, executed in 1536 for treason; Thomas More, who refused to acknowledge Henry VIII as head of the Church and was beheaded in 1535; the Princes in the Tower, Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, who vanished in 1483; and Guy Fawkes, arrested after the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Each of them represents a different era of power, betrayal, and resistance in English history.

Is the Tower of London really haunted?

Many Londoners and guides swear by it. Anne Boleyn’s ghost has been reported near the Chapel Royal, and some claim to see two small figures near the Bloody Tower-believed to be the Princes. The Beefeaters themselves won’t confirm or deny, but they’ll tell you the lights flicker in the White Tower on quiet nights. Whether it’s real or not, the stories have lasted for centuries because they reflect how deeply these events are woven into London’s soul.

Can you visit the actual prison cells?

Yes. The Tower’s prison cells are part of the public tour. You can see Guy Fawkes’s tiny cell, the Queen’s House where Anne Boleyn was held, and the chambers where nobles were kept under house arrest. The cells are small, cold, and often damp-just as they were centuries ago. Some even have marks on the walls from where chains were attached.

Are the Crown Jewels real?

Yes. The Crown Jewels on display are the originals, used in coronations and state ceremonies. The Imperial State Crown, which contains the Black Prince’s Ruby and the Cullinan II diamond, has been worn by every monarch since 1838. They’re guarded by armed sentries and laser systems, and have only been stolen once-in 1671-by Colonel Thomas Blood, who tried to flee with the crown under his coat.

How do locals in London feel about the Tower of London?

Londoners have a complex relationship with the Tower. It’s a symbol of power, but also of suffering. Many see it as part of their heritage-not just a tourist attraction. Locals from Tower Hamlets or Southwark often take visitors there not just to see the jewels, but to tell the stories of the people who suffered inside. It’s a place of pride, sorrow, and memory all at once.

Comments (8)

- Yzak victor

- November 8, 2025 AT 08:51 AM

The Tower’s prison cells are way more chilling than most museums let on. I’ve stood in Guy Fawkes’s cell - barely big enough to stretch out - and felt the weight of what they did to people just for thinking differently. The chains on the walls? Real. The damp? Real. The silence? Even more real. This isn’t just history - it’s a warning written in stone and rust.

And let’s be real: the Crown Jewels are flashy, but the real treasure is the stories they tried to bury. Anne Boleyn’s last words weren’t about revenge - they were about peace. That’s the kind of strength that outlives kings.

Also, the Beefeaters? They know more than they say. Ask one about the rats. They’ll tell you the dungeons used to flood twice a year. That’s not folklore - that’s engineering failure meets human suffering.

Don’t just take photos. Stand still. Listen. You’ll hear something.

- Kiara F

- November 9, 2025 AT 18:03 PM

People romanticize this place like it’s some kind of gothic romance novel. Anne Boleyn was a manipulative schemer who seduced a king and then got what she deserved. Thomas More was a stubborn zealot who let his religion blind him to reality. The Princes? Probably died of natural causes - no need to blame Richard III for every bad thing that happened in the 15th century.

This whole post reads like a tourist brochure written by someone who watches too many Netflix documentaries. The Tower wasn’t evil - it was a tool. And tools don’t have morals. People do.

- Nelly Naguib

- November 10, 2025 AT 08:37 AM

OH MY GOD. I JUST GOT CHILLS. Like, actual goosebumps. I swear I saw Anne Boleyn’s ghost last summer when I visited - I was standing by the chapel and the air just… froze. No wind. No birds. Just silence. And then - a whisper. Not words. Just a sigh. Like she was saying ‘I’m still here.’

And the Bloody Tower? Don’t even get me started. I stood at that window for ten minutes and my phone died. No battery. No signal. Just me and the ghosts. I left a red rose there. No one else did. I felt like I was the first person in 500 years who actually *saw* them.

This isn’t a tourist spot. It’s a shrine. And if you’re not crying by the end of the tour, you’re not human.

Also, the Crown Jewels? So shiny. So fake. But the chains? Those are real. And that’s what matters.

- Nicole Ilano

- November 12, 2025 AT 03:29 AM

From a forensic historiography standpoint, the narrative architecture of the Tower’s mythology is heavily contingent on Tudor propaganda and post-Reformation hagiography. The ‘hauntings’ are psychosomatic projections of collective trauma, mediated through Victorian gothic revivalism and reinforced by performative tourism.

Also, the Crown Jewels are not ‘real’ in the ontological sense - they’re symbolic capital, reified through institutional legitimacy. The fact that you think the chains are ‘real’ means you’re conflating materiality with meaning. The real artifact is the narrative. Not the stone. Not the metal. The story.

And FYI - the ‘damp’? That’s not medieval moisture. It’s modern HVAC failure. The Tower’s climate control is a disaster. I’ve done the thermal imaging. It’s a mess.

- Susan Baker

- November 13, 2025 AT 08:20 AM

Let’s break this down statistically. The Tower of London has recorded 127 documented executions between 1100 and 1747, with 38 of those being nobility. The average time between arrest and execution for high-status prisoners was 14.7 days - significantly shorter than commoners, who averaged 42.3. This suggests institutional prioritization of elite elimination - faster, quieter, more efficient.

Also, the ‘ghost sightings’ correlate strongly with atmospheric pressure drops below 990 hPa and relative humidity above 85%, which explains why they’re reported mostly in late autumn and winter - when the Thames fog rolls in and the stone retains moisture, creating auditory pareidolia. The ‘whispers’? Wind through narrow archways, not spirits.

And the Crown Jewels? The Cullinan II is 317.4 carats. It was cut from the largest gem-quality diamond ever found. The Black Prince’s Ruby? Actually a spinel. Misidentified since the 14th century. The entire collection is a masterclass in misattribution and mythmaking.

So yes, the Tower matters. But not because of ghosts. Because of data. And the data doesn’t lie.

- diana c

- November 14, 2025 AT 13:57 PM

It’s funny how we turn suffering into spectacle. We line up to gawk at the chains, then buy postcards of the Crown Jewels. We call Anne Boleyn a martyr, but we’d have silenced her in a heartbeat if we’d lived then. We call Thomas More a saint, but we’d have called him a traitor.

The Tower doesn’t haunt us because of ghosts. It haunts us because it’s a mirror. We still imprison people for speaking out. We still execute ideas we can’t control. We still let power decide who lives, who dies, and who gets remembered.

That’s why it still feels alive. Not because of whispers in the dark - but because we haven’t changed enough to make it obsolete.

Next time you visit, don’t look at the stones. Look at yourself.

- Shelley Ploos

- November 15, 2025 AT 15:42 PM

I’ve taken my students here every year for the last 12 years. Not for the jewels. Not for the ghosts. For the chapel. It’s small. Quiet. Unassuming. No banners. No crowds. Just names carved into stone - Anne, Thomas, Guy, and dozens more who never made it into the history books.

One year, a girl from Afghanistan sat there for 45 minutes. She didn’t say a word. When she left, she left a single pebble on the floor. I asked her why. She said, ‘In my country, we leave stones for those who disappeared. So they’re not forgotten.’

The Tower isn’t just English history. It’s human history. And we’re still writing it.

Bring a quiet heart. Leave your phone. And listen.

- Haseena Budhan

- November 16, 2025 AT 16:29 PM

they say the princes are haunted but like... what if they just got kidnapped and no one cared enough to look? like we dont even know what happened. its so dumb how we turn everything into ghost stories.